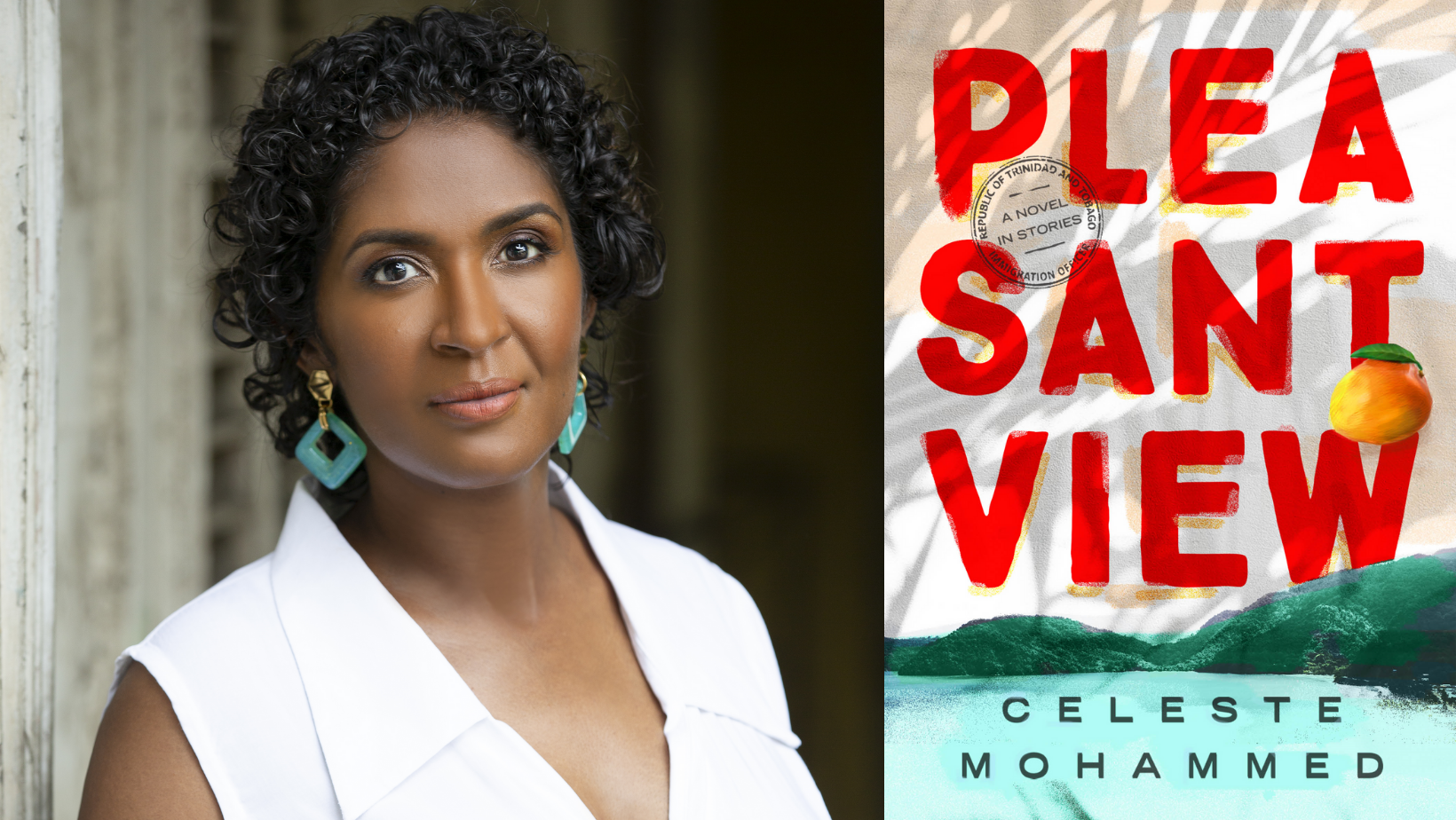

SPQ’s Author Spotlight: Celeste Mohammed, author of Pleasantview, A Novel in Stories | Interview conducted by Bonita Lee Penn

“Mohammed’s writing is smart, funny, and enlivened by everyday Trinidadian vernacular, creating rich and lively portraits of a range of Trini characters. A formidable debut, Pleasantview’s razor-sharp observations of misogyny and the abuse of power are leavened by humor and a pitch-perfect ear for the language of human foibles.”

—Tony Eprile, author of The Persistence of Memory

Bonita Lee Penn: I remember you sent me a couple of your short stories, and I immediately thought I need to read more about these characters. Recently, I was honored to read your debut novel-in-stories, Pleasantview, and found those short stories to be a part of the book. In the beginning, did you write the individual short stories with the intent to link them as one?

Celeste Mohammed: You know the saying, “God works in mysterious ways”? Well, that’s basically what happened with this book. Six out of the nine stories were written as coursework during my MFA study at Lesley University. I was simply writing whatever came into my head, just to meet the monthly deadlines. I had a newborn baby, had just moved into a new home which was unfinished and still under construction, I was trying to recover from a difficult pregnancy. There was so much going on in my life, I had no time to masterplan anything. I just wrote. It wasn’t until it was time to pull together my thesis that I sat with the text and realized the muse had been operating all along. I saw that the stories were loosely linked and that with slight amendments the linkages could be strengthened. Post-graduation, I was fortunate to find an agent and when she went out with the book, it was soundly rejected by about twenty publishers, one of the reasons being: the collection wasn’t linked enough. So I sat with the text again, and crafted three more stories to round off the book into what it is today: something that reads like a novel.

BLP: Some readers may pick up your book and assume, since the location is on a Caribbean island, that this will be a feel-good, cute romance island type story; how do you think they will receive this side of the island story? What would you like the readers to take away?

CM: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has famously talked about “the danger of a single story.” I think she speaks for all so-called “Third World” countries when she says: “The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete.” I recognize I have a choice when writing to an international audience about Trinidad and Tobago. I can write into that single story: fun in the sun. Or I can write another side of the story, show another face of the prism. I can write using the Caribbean as merely “setting”, or I can write the Caribbean as “subject”. This book makes it clear which choice I’ve made. I live here, I navigate life here on a day to day basis. I think I owe it to myself to tell a bigger truth.

BLP: What possessed you to write Pleasantview and share with us a little about the story and the story world you have created and how you developed the novel’s setting?

CM: In my mind, Pleasantview is a microcosm of Trinidad. I find Trinidad to be a fascinating place, and although I was born here, I still don’t fully understand it. Creating a town where I could explore some of the issues and archetypes encountered in wider society seemed like a useful fish-bowl type experiment. Of course, this has been done before by VS Naipaul in his famous Miguel Street. But Trinidad is no longer the place it was in the mid-20th century, when he set up his fish-bowl. Nostalgia has its place on our bookshelves, but what is more urgently needed, I think, is to examine 21st Century Trinidad.

So, come visit Pleasantview district. Come during election season; see how a candidate’s character means nothing. Come on the night one potential candidate sets out to slaughter endangered turtles – just for fun. Or on the day another candidate, Mr. H, beats Gail, his “outside-woman,” so badly she ends up losing their baby. Come on the night of the political rally, where this grieving woman exacts a very public revenge. Stay a while, and see how this single event has a trajectory far beyond the lives of the immediate actors. See how it brings Mr. H’s estranged daughter and Gail’s ambitious brother back home – just when they thought that, by getting on an airplane, they had escaped the suffocation of Pleasantview. Watch the old “seer-woman,” Miss Ivy, weave her way through all this bacchanal. Mourn the marriage of another couple, Ruth and Declan, Pleasantview upstarts who dared to think that, with education, they could achieve a better life. And, in the end, witness one lost boy introducing another lost boy to a gun and to an ideology which will help him aim the weapon.

Do we infect where we live, or does where we live infect us? That’s the question I am posing in this book. Are these people innocent, guilty or just in the wrong place? You decide.

BLP: Which character(s) in the novel was the most challenging to write? Whose story was a challenge and why? Do you have a favorite chapter or character(s)?

CM: Writing “Home”, the story of Kimberley, was the most difficult. It is a lesbian story that’s not really a lesbian story – but it took me a while to figure that out. I was so hung up on wanting to respectfully and authentically portray this person who is an “Other”, I was losing sight of the heart of the story. In the end, I realized she is not “Other”; she is me, she is you, she is anyone who has struggled with self-acceptance and the weight of family expectations.

My favorite character is Miss Ivy, the grande dame of the village. I think every village or community has a Miss Ivy, the older lady who has seen it all, who is the oracle of all wisdom, who is not afraid to tongue-lash anyone, who can be as eccentric as she wants. I felt most free when I was writing her.

BLP: Several videos are promoting your novel. Whose idea was this? Are there some conversations about adapting your novel into a movie?

CM: It was my idea to do the videos. I had seen a few book trailers before, but they were kind of writerly and abstract. I felt that tone was incongruous with what I’m trying to do with this book. Pleasantview is meant to be accessible literary fiction – you shouldn’t need a University degree to read and enjoy it. So I wanted to do these book trailers which made that clear. I picked the three award-winning stories and, for each, highlighted one key scene.

I wish someone would ask me about making the book into a movie! But no, that hasn’t happened…not yet, anyway (fingers crossed).

BLP: When did you first notice your natural ability to tell a story; when did you know your words held the power to have people stop and listen? When is your earliest memory of being a compelling storyteller?

CM: I have been writing stories for as long as I can remember. I always did well at English Composition in primary and secondary school. My teachers told me I had a gift. I just didn’t know what to do about that. When I was growing up, during the late 70s-early 80s in Trinidad, becoming a writer is not something to which you aspired. Understand that we broke away from Britain and became a Republic in 1976, understand that under colonialism the only way for non-whites to advance was entering the professions and the oil industry. No wonder our parents felt the only option for us was to become doctors, lawyers or engineers. So I did what was expected of me – I became a lawyer – all the while harboring this secret desire to be a storyteller.

BLP: Does writing energize or exhaust you?

CM: I would say both. There’s a cycle of energy creation and depletion involved in writing, at least for me. The energy which compels and propels me to the keyboard becomes spent there. I stop then – it may be one, three or four hours later. I am mentally exhausted. Afterwards, I go about my day with a whirring in my head, as the sights and sounds of life replenish that creative energy. Next day, I’m back at the keyboard. And so it goes, and so it goes, for weeks or months until the project is finished.

BLP: Your book is published by Ig Publishing a New York-based press devoted to publishing literary fiction and political and cultural nonfiction. How did this publishing deal come about?

CM: Pleasantview was roundly rejected by all the big publishing houses, and then by all the smaller ones my agent approached. I spent a few years trying to peddle the book myself. Then, when the pandemic happened in 2020, I said, “Look, you’re trapped at home. Why not try to figure out how to self-publish this book.” So, I was heading down that road when a writing mentor of mine asked if I’d given her publisher (Ig Publishing) a try. The rest is history.

BLP: How was the editing process for your book? The publisher is in the United States, and you are a Trinidadian writer who uses Trinidadian vernacular in the book. Did you have an editor who was in tune with your aesthetic?

CM: The editing of the storycraft is a different discipline to the editing of the text and vernacular etc. Storycraft – how to successfully tell a story – is based on universal principles that any experienced editor can bring. I have been fortunate that my writing mentors/editors have been the same persons since MFA days. So they understood me and my work well enough to fearlessly critique it. I see it as an advantage to have editors who are not Trini – because if I can satisfy them, I can satisfy a non-Trini audience. The vernacular and copyediting of the text, however, was done by an experienced local writer/editor.

BLP: You also attended a graduate program in the States, Lesley University in Cambridge, MA; what type of experience did you have in grad school as a Trinidadian writer? Did you have any challenges with cohorts and mentors understanding your aesthetic? How did this experience affect you as a writer?

CM: Yes, as we know, MFA workshops can be brutal. Even more so when you’re the only small-islander in the class. Not everyone is willing to make an effort with a different culture. But I took it as a challenge and an education: if I wanted to have any international impact as a writer, I was going to have to learn to reach people who don’t speak my language, who are set in their ways. Learning how and to what extent to compromise and make accommodation for a non-Trini audience was a big take-away from Lesley. I am grateful for it. Overall, I was well received and well treated, though.

BLP: Do you have a community of writing friends; how do they help you become a better writer?

CM: I am not part of a writing group that exchanges work. But Lesley has allowed me to become friends with so many writers that if and when I need help, I know exactly who to approach. My Lesley cohort is close-knit and very supportive.

BLP: What is the most challenging part of your artistic process?

CM: Getting the story out onto the page is the most difficult part. You see, for me, it isn’t an intellectual process which I can plot and plan from Introduction to Conclusion. For me, it is almost akin to being a stenographer, I am listening for the story as I type. There is a through line, or should I say “true line”, to every story – an internal logic that guides and determines every intellectual choice I subsequently make during revision. But first, I have to find that line. That’s why I can’t listen to music while writing – before, to get into character, yes, but not during. I have to keep those auditory channels free to listen for the story, the voices, the rhythms etc. It’s so easy to lose signal and go off in the wrong direction, or to find myself going in circles. So exhausting to keep listening and inching forward, following that line, even when I don’t like where it is taking me.

BLP: How has your family supported your career as a writer? What do they think about the awards you have received? Are they ready for a celebrity in the family?

CM: My husband has always been supportive of my career as a writer. As for the wider family, like a typical West Indian family, they didn’t understand at first. As I’ve explained earlier, the perception might have been: Who leaves a law career to sit at home and write? I don’t think that was coming from a bad place, but rather from a place of concern for my wellbeing and independence as a woman.

The awards? Come on, you know West Indian families are permanently unimpressed (Ha, Ha!)

BLP: What new projects are you working on; where can the readers purchase your book?

CM: I am working on a children’s book. I’ve had to read so many of them over the last few years since having my daughter, it seemed a natural thing to attempt. I would like her to see herself and her culture represented in the pages of those pretty picture books she so adores.

Pleasantview comes out on May 4 but is available for pre-order now. It can be purchased wherever books are sold. Pop over to my website www.thecursivem.com where there are clickable links to a few places where you can order.

Check out the Pleasantview Book trailers:

Episode 1, Loosed: https://youtu.be/5WeTFTNwXno

Episode 2, Six Months: https://youtu.be/MBV5tYddkiU

This article was first published in Soul Pitt Quarterly Print Magazine (Spring 2021). Copyright Soul Pitt Media. All Rights Reserved.