|

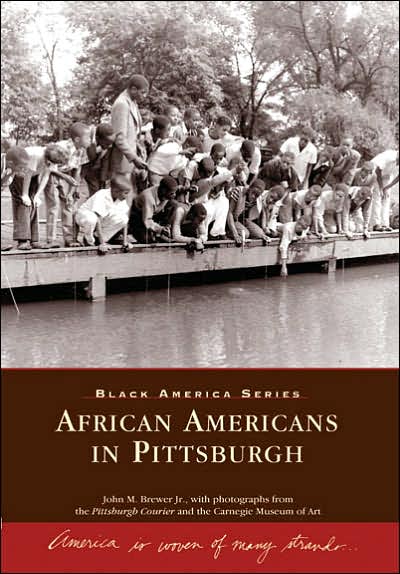

John Brewer: African Americans in Pittsburgh

Interview- Page 2

There's a chapter describing the jazz era and talent pool found in the Hill District. To musicians,

Pittsburgh

was known as the Gateway. You couldn't play

New York

without first being accepted in

Pittsburgh

. This was considered the center of the talent pool for great jazz players; sports figures; artists and the medical field.

By this time the African Americans were becoming a real entity in the City of

Pittsburgh

, in fact, they were independent of the economy of the City. This independence set up an interesting scenario, the counter under the name of Urban Redevelopment , under the name of We-Gonna-Help-Those-Folks-Out. The start of the renovation or the Destruction of 60 to 80 blocks of the Hill District to build a big blimp called the Civic Arena. All the small businesses which had stabilized the community financially were completely wiped out. This impacted the black community considerably and also caused the flight of the middle class to other communities such as

Homewood

and the

East Liberty

areas.

The Greater Pittsburgh Improvement was organized to fight the job discriminatory practices of local businesses, a fight the local NAACP didn't have enough muscle to continue. The organization staged their first successful boycott, along with becoming a voice that scared the local powers-that-be. One of their fights was confronting the integration of the

Highland Park

swimming pool. An attorney by the name of Smith, who would later become Judge Henry Smith, but at this earlier time, was the organization's attorney. He presented a petition to the Mayor of Pittsburgh to have African Americans admitted to the

Highland Park

pool. The Mayor was out of town and his assistance who was scared to death signed the petition. This was one of the pools integrated but it wasn't the toughest. The toughest was the pool was on Paulson Avenue, where the Italians lived. The organization turned their focus to Forbes Field, where blacks weren t allowed to sell food, (whites stating the black skin would rub off on their food) they were also successful with this fight. Their slogan was You Don't Buy Where You Can't Work.

That's some of the general background on the logic of the book. I received a lot of positive comments from people who see people they knew. It s good for the soul to look back. To my surprise the strongest sales have been to the young people who are curious to know what people looked like, how they acted, how they dealt with living in the community. They were surprised by the many prominent black people who looked like people in their families. Many of the older customers use it as an ancestral connection by buying books to past on to their grandchildren.

I asked Mr. Brewer what contributions he feels his book would make in our educational system.

I participated in a reading and writing book fair at

Westinghouse

High School

earlier this year. There were approximately 15 to 20 prominent local people sharing with the young people the importance of our culture, reading and writing. I used my book as a teaching tool to demonstrate to the class the importance of our history and their response was overwhelming. I feel we need to move beyond the traditional educational borders, we've an exceptional problem within our community, as many are not turned on by reading. I recited to the class Carter G. Woodson's words, A man without culture is a man doomed to destruction. I then asked the students where they wanted to be in ten years and it was sad to hear one of ten had a definite plan.

I asked Mr. Brewer what important factors if any from the past if were implemented today would help uplift our communities.

I believe a couple of things would help but they can't be regained. To start back in the day when were in the same pot, even though some of us were lower Hill and others were Sugar Top we were still in the same pot. When we integrated we separated and when we separated we dissipative. When were in the same mix we were forced to do business with ourselves. We had a better examination of who we were. We have lost the essence of loving ourselves. If you love yourself, you're not going to kill someone who looks like you.

Starting in the 1960's we moved into the 'I' age and went crazy. We haven't gotten it together since.

There's a serious gap in our ancestry history. What I ask young people to do is simply get your Grandmother's Bible, the big family scrap book and start piecing together your family. The book is simply an attempt in getting us to recommit back to our own culture.

Question to Mr. Brewer, are there any strong points from the past that has survived?

Yes, the beat goes on. The music still goes on. It's basically still a three or four pace beat which even though the rappers feel they invented it, comes from our past. The music and the beat have survived around the world. In

Pittsburgh

the beat still exist. The beat is what heals us; it causes us to look at who we are. We can still feel warmth from the music and from warmth come love. I think it has survived.

We are sitting in the Trolley Station Oral History Center. Tell us a little about the Center.

The pictures on the walls are what you'd call our memory board. It's a device to tell your history. Africans in this country still use oral history 'lukasa' as a way to convey their history. It wasn't until the 20th Century that our history started to be written.

The concept came about when I first acquired the building in the 1980's. Trolley cars were the main means of early transportation between communities. This has played an important role in connecting people and communities with each. Much of the black male population in

Pittsburgh

worked on the trolleys as highly skilled artisans. These black men literary built

Pittsburgh.

I use this part of the building to preserve the pictorial history of the trolleys and it's affect on life.

John M. Brewer, Jr., is a historian and consultant for the Pittsburgh Courier archive project, a consultant for the Carnegie Museum of Art's Charles Teenie Harris photograph project and the curator and founder of the

Trolley

Station

Oral

History

Center

and author of the Black American Series African Americans in

Pittsburgh.

His book may be purchased:

Barnes & Noble; Borders, Dorsey's Records,

John

Heinz

History

Center

and the

University

of

Pittsburgh Book Store

.

|